Features

The Hague Design System Is Undoubtedly Useful, but National Formalities Still Exist

Published: January 25, 2023

Ivy Estoesta Sterne, Kessler, Goldstein & Fox P.L.L.C. Washington, D.C., USA Designs Committee

James Aquilina Quarles & Brady LLP Washington, D.C., USA Designs Committee

Israel Jimenez Breakthrough IP Intelligence SC Mexico City, Mexico Designs Committee

Yoonkyung Cho Y.P. Lee, Mock & Partners Seoul, South Korea Designs Committee

Tony Chang Muncy, Geissler, Olds & Low Alexandria, Virginia, USA Designs Committee

Hank Leung Bird & Bird Hong Kong SAR, China Designs Committee

In February 2022, China joined the Hague System for the International Registration of Industrial Designs, which provides a streamlined process for obtaining and managing industrial design protection in multiple jurisdictions. Now covering the entirety of the ID5 (the five largest industrial design offices worldwide: China, the European Union, Japan, South Korea, and the United States), plus other significant markets such as Canada, Israel, Mexico, and the United Kingdom, the Hague System appears to be a powerful procedural tool.

The Hague System allows an eligible applicant to file for industrial design protection in up to 94 countries through a single international design application (IDA), without engaging local counsel. To be eligible to file an IDA, an applicant must be a national of, domiciled in, or commercially established in one of the 77 contracting member parties, which are listed here. Thus, reduced initial transactional cost is a key advantage of filing an IDA designating multiple jurisdictions over filing separate national applications across multiple jurisdictions. Once issued, an IDA is also simpler to maintain, as the Hague System permits applicants to pay a single combined renewal fee for an IDA designating multiple jurisdictions.

However, the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) examines the contents of an IDA only for formalities; whether an IDA will proceed to registration in the individual designated jurisdictions will depend on its satisfaction of the particular laws and rules of each designated jurisdiction. And because those rules are not harmonized across jurisdictions, unpredictable and inconsistent hurdles may result after the filing stage. Addressing those hurdles typically requires engaging local counsel, which can cancel out the upfront transactional savings of filing an IDA.

The sections below summarize the various possible hurdles, depending on which jurisdictions the IDA designates.

Inadequate Visual Representations

An IDA must include visual representation(s) showing the claimed design. The Hague System provides technical requirements for the file format of the representations but imposes no substantive requirements or restrictions on the number or types of representations to include in an IDA. This flexibility, however, may pose issues at the substantive examination stage in some jurisdictions. For example, if an IDA includes only the following representation of a design, the design may register in the UK and the EU—which do not require more than one view of the claimed design—but might not in countries that require specific types of views (e.g., South Korea and Vietnam, or that do not consider a single view of certain 3D designs to disclose the claimed design completely (e.g., the United States).

Some jurisdictions also prohibit representations including discontinuous shadow lines intended to show contour (e.g., China), while others encourage their inclusion (e.g., Japan), and still others (e.g., the United States) require their inclusion for certain 3D designs.

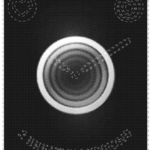

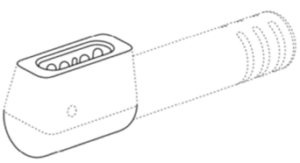

Jurisdictions’ requirements for visual representations for 2D designs, like graphical user interface (GUI) and computer icons (collectively known as computer-generated designs), also vary. For example, some ID5 countries and the UK do not require visual representations to show a device on which a computer-generated design may be displayed, while the United States and Mexico require representations to show a display screen, though it may be drawn in broken lines and unclaimed, as shown below.

USD957440 |

MX 49023 |

Incorrect Product Indication and Insufficient Written Description

An IDA must include a product indication to identify the article embodying or to which the claimed design is applied. This seemingly simple formality can be challenging when filing an IDA that designates multiple jurisdictions that take opposite views on whether the selected product indication defines the scope of protection of a design. In some jurisdictions like China, the selected product indication can define the scope of protection, while in others like the EU, it has no effect on scope. Moreover, there is ongoing debate in the United States about whether the IDA title and written claim, which must match in terms of the type of article identified, limit the enforceable scope of a U.S. design patent.

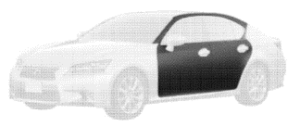

Selecting a product indication for a portion of an article (partial design) can also be challenging. Take for example the following partial design:

USD654419

While some jurisdictions (e.g., the United States) prefer that applicants use the complete article “car” as the product indication, others (e.g., China) might instead require a product indication that refers to both the claimed portion and the overall finished article in which the part is located.

Similar challenges arise for computer-generated designs, which some jurisdictions (e.g., China and the United States) do not view as a product or an article of manufacture. In those jurisdictions, the selected product indication must refer to a physical product, like a display screen, on which the computer-generated design may be displayed. In other jurisdictions (e.g., the EU and the UK, the product indication need not refer to a physical product, therefore permitting the production indication “graphical user interface” or “icon.”

An IDA may include additional descriptions specifying the view of the article (e.g., “front view”), clarifying characteristic visual features of the design (e.g., lines intended to show contours or the appearance of translucency or contrasting surface texture), and/or exclusion of portions of the article from the claimed design. However, some countries require this optional formality in an IDA for certain types of designs. For example, China, Japan, and South Korea require additional description specifying the intended use of and/or manner in which a user interacts with the claimed computer-generated design. However, no such description is required (and in fact may attract an objection) for computer-generated designs in the United States.

Inconsistent Treatment of Partial Designs

Partial designs are eligible subject matter for protection in many jurisdictions that are party to the Hague System, including all of the ID5 countries, Mexico, and the UK. However, the applicability and disclosure requirements for partial designs vary in many of those jurisdictions.

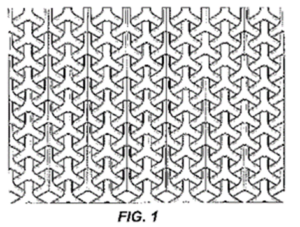

For example, in Mexico, a partial design must adhere to a complete product, and an applicant cannot omit any unclaimed parts from the drawings and instead must show them in dashed/dotted lines. Thus, while the following disclosure for a chair pattern is acceptable in the United States, it may not be acceptable in Mexico without a dashed/dotted line showing a complete chair.

U.S. Pat. No. D677,946—Pattern for a Chair

Additionally, China’s Patent and Industrial Design Office (CNIPA) has not yet published final guidance on how it will examine partial designs. As of December 29, 2022, only the Draft Implementing Regulations of Patent Law (issued on November 27, 2020) and the Second Draft Patent Examination Guidelines (issued on October 31, 2022) have been published, with final guidance expected to issue in 2023.

The Second Draft Patent Examination Guidelines indicate that a partial design may be eligible subject matter if it forms a relatively independent part or constitutes a relatively complete unit. See id., Section 7.4, Chapter 3, Part I. The same Guidelines also indicate that the following types of partial designs may be ineligible for industrial protection in China: “an irregular part of a spectacle lens arbitrarily obtained” and “the pattern on motorcycle surface.” Id. Thus, the following partial designs, which are eligible for protection in the United States, might be ineligible for protection in China.

U.S. Pat. No. D671898 |

U.S. Pat. No. D613155

|

Submission of Formal Documents

The WIPO Digital Access Service (DAS) is an electronic priority document exchange system that allows priority and similar documents to be provided to participating offices without having to obtain and submit printed certified copies of priority documents. WIPO DAS can therefore significantly ease the burden of filing priority documents. According to WIPO’s Hague Yearly Review 2021, more than 50 percent of IDAs filed in the years 2017–2021 included a priority claim.

However, of the 77 contracting parties to the Hague Agreement, the WIPO DAS is only available to 13 offices, with some participating only as a depositing office (DO): Canada, China, the EUIPO, France (DO), Georgia, Israel, Italy (DO), Japan, Mexico, Norway, South Korea, Spain, and the United States. Some offices, like Mexico’s, separately require submission of a translated priority document, which necessitates engagement of local counsel.

Deferring Publication

An IDA can include a request that its publication be deferred for up to 30 months from the filing date. An applicant can thus make strategic use of such deferred publication. For instance, this deferment can allow the design appearance to be kept confidential until the intended date of release of the actual designed product into the market. This deferment of publication is additionally useful when the applicant plans to register other similar designs. In this case, the applicant can use the deferred publication to prevent the publication of the IDA from being cited as prior art against such additional design filing.

However, not all jurisdictions allow deferred publication, and those that do provide differing maximum deferment periods. For example, the maximum period for formal deferment is 30 months (measured from the application filing date or the earliest claimed priority date, if any) in the EU, three years in China, and 12 months in Denmark, Finland, Israel, Norway, and the UK. Still other jurisdictions, like Mexico, Turkey, and the United States, do not permit deferred publication at all (although U.S. design applications do not publish prior to issuance as a U.S. design patent). If an IDA designates any jurisdiction that does not allow deferred publication, deferment is not possible.

Grace Period

Lack of harmonization in the grace period available to file a design application after public disclosure of a design also poses formidable challenges to applicants seeking design protection through a single IDA. For example, while most ID5 countries, Mexico, and the UK recognize a 12-month grace period for public disclosures made with or without the applicant’s consent, China’s grace period for designs is six months and available only for disclosures in certain situations, like disclosures by the applicant “at a national emergency for public interest,” “at an international exhibition sponsored or recognized by the Chinese Government,” “at a prescribed academic or technological meeting,” or “certain disclosures of the invention obtained by a third party from the applicant or the inventor.” See “Patent Law of the People’s Republic of China,” 2021, Article 24.

Some jurisdictions (e.g., the EU, Mexico, the UK, and the United States) also have no formal requirements to take advantage of the grace period, while others (e.g., China, Japan, and South Korea) require submission of a declaration and/or supporting evidence. In China, Japan, and South Korea, this documentation may be submitted with the IDA, or after the IDA is filed through a local representative, within varying time periods. See WIPO’s Guide to the Hague System: International Registration of Designs Under the Hague Agreement, especially “Item 15: Exception to lack of novelty.”

Conclusion

China’s long-awaited accession has, at least on the surface, cemented the Hague System as a very useful procedural tool for global design filings. However, the many inconsistent requirements and practices among the national industrial design offices still require users to cater to the idiosyncrasies of national formalities, making practical use of the Hague System challenging for practitioners who are not familiar with local practices and requirements. These inconsistencies may cause applicants to abstain from using the Hague System altogether when planning an industrial design filing strategy. Alternatively, applicants unaware of such inconsistencies may encounter cost increases, delays, or (worst yet) an insurmountable refusal in some jurisdictions in the granting of design protection.

Therefore, applicants considering whether to file an IDA should be aware of its potential pitfalls, and industrial design offices should continue to work towards aligning their local design rules and laws with the best international practices (e.g., INTA’s Model Design Law Guidelines) to improve the predictability and outcomes for applicants that choose to file via the Hague System.

Although every effort has been made to verify the accuracy of this article, readers are urged to check independently on matters of specific concern or interest.

© 2023 International Trademark Association